WHEELS OF FORTUNE

. . . from bananas and flannel to media drivel

. . . a personal hystery of the mountainbikeby Dink Bridgers

copyright1997

If you are interested in updates to this story, click on HYSTERY.In April of 1975 my wife and I moved into the Haight Ashbury of San Francisco. The Haight was low rent, in transition from heroin and hippies to homosexual revolution and yuppie scum, filled with a strange mixture of shell shocked and pitifully handicapped Vietnam war veterans, junkies, psychedelic drug crazies, child prostitutes, hedonistic artsy-fartsy types, trust fund babies, extremely flamboyant gays, and struggling musicians like myself.

Pregnant, broke, and too young to be frightened by these prospects, we moved into a rundown, leaning Victorian on Lyon Street across from houses where Charlie Manson and Janis Joplin had lived a few years before. We furnished the dump with found objects and an eclectic selection of irrational homemade furniture constructed from recycled Victorian gingerbread redwood lumber fragments, ancient crumbling quilts, doilies, and antique textiles gleaned from dumpsters, thrift stores, and the Marin City flea market in Sausalito.

We were used to the poverty of boat living in Amsterdam, so this psychedelic slum just off of the Panhandle of Golden Gate Park was a step up from floating on a psychedelic open sewer. In Amsterdam we took a crap in a bucket in the same room we prepared food and dumped it out of the window into the canal as the junkies across the street lined up to puke from their morning fix. In our Haight Ashbury apartment, even if the bathroom had no floor, at least we had a toilet, and, even if the kitchen was simply an elevated platform in the corner of our living room where it rained just like outside, at least we had a rattling, frosted-up refrigerator, and a leaky gas stove.

Hell, we were in love. We managed to turn even the most depressing slum hole into a love nest.

Days after settling into the apartment on Lyon Street I bumped into an old friend from Amsterdam in the Panhandle and, on the spot, he offered me a job with a crew of wild queers, painting Victorian Gingerbread houses fancy colors for the upscale infestation of trust fund immigrants of the upper Haight that would soon turn the neighborhood into a place where you could buy espresso, ice cream, cake, and tacky clothes in shops with fancy awnings, but couldn't find a place to do your laundry or purchase toilet paper.

A couple of weeks later I ran into another old friend, who sold me a wheezing, classic two-tone 1962 Chevy Bel Air convertible for $200.

Within hours of coming home from the hospital for the birth of my daughter, Bubble, I met Dago in a dumpster. Dago was a very unique fellow, very friendly. He never bathed, wore only a leather loin cloth, and looked just like the picture of Jesus that my grandma hung in her living room, only with more dirt, less clothing, and a much nicer smile. The very next week Dago arrived barefoot and practically naked at my doorstep with an old English Dunelt ten-speed road bike he had upgraded with flea market Campy stuff, and sold it to me for $25.

So, all toll, within a month of landing in San Fran, I had a family, an apartment, a car, a job, an assortment of very weird and special friends, and a bike.

Meanwhile, over in Marin County, things were brewing. Years later in Moab I found out just how crazy Marinites actually were. I was told a bogus story by an acquaintance--of two fellows who signed up for a cyclocross race in Marin and were turned away. I printed the story here and left it to mellow with the rest of this babble.

In 2008 the acquaintance, who had called himself a "race promoter" emailed to say the story was a "complete fabrication" and was the reason that I had no friends, forgetting that it was this very fellow who told the story to me in the first place. So, here it is, the lie verbatim: "These guys just walked up with these two bikes. I had never seen anything like them, and, at the time, I never wanted to see one again. These things must have weighed fifty pounds. They were old cruisers, decked out with double chainrings, derailleurs, and drum brakes. I ran them off and never saw them again. Gary Fisher claims to have invented the off-road bicycle in 1976, but these guys had him beat by a year."

It is such an interesting feature of personality that people believe their own lies as they tell them, then don't remember the lie later, because, well, it's a lie, not in the same memory bank as the truth, which is far more important, I guess. But, then, Marin breeds liars, cheats and thieves. I lived in Marin for a year in 1971. The nightmare of those months imprisoned in the redwoods with people conditioned to lie and cheat as a matter of life and business colored my vision of the county north of San Francisco forever. I must say that when I heard the fabricated story about the cyclocross race I forgot valuable lessons I had learned in 1971, trusting my Marinite "friend" and considering the tale to be the earliest known "record" of an off-road specific bicycle in Marin. Duh, the fault is my own. I should have known better than trusting someone born and raised in Marin County.

But frankly--all lies, lying and liars aside--I built an off-road bike when I was under ten years old. I took the fenders off of a 1948 Schwinn cruiser with 24 inch wheels, clipped some baseball cards (would be worth a fortune today) to the seatstays with clothspins, and farted noisily through the woods of my rural North Carolina home, happy as a lark. I never considered this act to be a landmark other than the strictly personal joy of it, because it wasn't a historic landmark. The men in my family had been doing this for generations. See the update of this story on the Dreamride bike sales web at HYSTERY for a picture of my granddad taken before World War 1, standing next to a Safety bicycle that could be mistaken for a modern singlespeed mountainbike. The picture pretty much puts the Marin fuss in perspective. Even the parts that the "founders" "invented" can be found in old cycling catalogs from the early 20th Century. Roller cam brakes? Suspension? It was all done before, but in cast iron.

My granddad and his friends rode off-road bicycles because there were no roads! For me the woods and fields were simply the best, safest places to ride, and the bike looked cool without the fenders, horn and lights. Cool breeds self-respect and pride.

Despite the fact that the Marinites didn't invent off-road cycling, they did know how to market it to hippies with money--The Yuppie Scum who have fucked up the entire world over the past 30 years.

One evening, some year or so after my move to San Francisco, I saw a feature on a local television show documenting a wild bike race on Mt. Tamalpias, the tallest peak in the Bay Area. A bunch of longhaired wildmen in open flannel shirts and blue jeans with bananas sticking out of their back pockets were blasting down a narrow, rugged, jeep trail on stripped down ancient cruiser bikes (much like the one I had when I was a kid), tossing rooster tails of dust into the air as they slid their heavy steel mounts sideways through the tight S-turns. I laughed as rider after rider lost control and crashed into the bushes bordering the road, mangling body and bike into tangled clumps of metal, flesh, and bone. My childhood regurgitated itself from deep inside the guts of my soul and memory and I thought to myself, "Now, this is great!"

The very next day I took my funky ten-speed onto a trail in Golden Gate Park. It was a reawakening, a religious experience, a deja vu that coughed up that long lost memory of putt putting that chopped Schwinn cruiser through the woods. This ecstacy was short lived when in less than a half a mile I blew a tire on a whoop-tee-doo through a grove of trees and bashed my nuts into the handlebar stem so hard that I damaged the manhood of my male offspring for three generations running. As I lay in the bushes, trying to find my breath, gut awash in throbbing pain, I decided to sell the bike and buy a skateboard. I was sure my descendants would be forever grateful.

True to my vision, Miki and I were soon using skateboards to commute all over town. I even built a custom board for our daughter Bubble, and within months of learning how to walk she was scooting down Haight Street with mom and dad. The guys in my punk band got the bug, too. We used our skateboards to cart gear in and out of the Mabuhay Gardens and the other funky punk clubs on Broadway, and spent the hours between sets boarding up and down the street, stoned out of our heads. When I found an old 8mm film camera the first thing I did was tape it to my skateboard. A skateboard is the most handy device imaginable.

Miki, Bubble, and myself were soon documented pioneers of the skateboard subculture when Thrasher Magazine interviewed us as "The Skateboard Family" and published a photo of the three of us trucking down Haight Street. They printed a completely fabricated rap with little Bubble and had her saying things like, "Yea man, my board is rad. I really like to shred the radical downhills and tear the asphalt sideways, man."

One Sunday in the park I took a really hard fall on my board. One look at the deep bruise on my hip and the skin missing from my palms and I instantly decided to sell the boards and buy BMX bikes for everyone, something that included brakes in the equation.

Within a few days of my impulsive, two-wheeled conversion, I found a beat-up 1947 Schwinn cruiser bike in a dumpster, and proceeded to ride it down to the beach and back on the trails in Golden Gate Park at least once a day. The bike's laidback geometry, upright position, and fat tires made the whoop-tee-doos a piece of cake, and, as I got stronger, I began to ride the technical trails around the cliffs at Lands End. The Lands End golf course was an especially attractive play area for moonlight fun with its rolling jumps, manicured berms, and smooth greens, and the thought of ruining some lawyer's putt really appealed to me.

Eventually I began to ride across the Golden Gate Bridge and through the National Recreation Area to the Marin City flea market in Sausalito on Sundays. This was the beginning of tradition still carried on by my friends in Frisco, even though the Marin City flea market is now sadly defunct.

I eventually traded my skateboard for a Redline BMX. I installed a custom rear wheel and a six speed drivetrain on the bike for Bubble and she took to it like a duck to water. I then proceeded to blow up both knees by taking on longer rides than I could handle on a heavy singlespeed.

Meanwhile, the Marin downhill race, Repack (named such because each rider had to repack his coaster brakes with grease after every run), continued to squeak into the news now and again, increasing the demand for cruiser bikes and turning Mt. Tamalpais into a deathtrap for hikers. Old, heavy, beat-to-shit Columbia and Schwinn Excelsior frames were soon going for $300 a piece at the Marin City flea market. It was rumored that a few custom road bike builders in Marin were fabricating off-road bicycles from scratch to feed the increasing demand.

One Sunday I saw a custom built prototype ATB for sale in the flea market, drawing spectators like a couple of dogs humping. The bike was built up with fancy euro lug work, a TA touring crankset, campy road touring derailleurs, and a thick sheep skin pad on a Brooks springer saddle. I took it for a test spin around the market and within a few feet I was sick as a kitty stung by a scorpion.

The next day I laid-a-way a couple of Schwinn King Stings for myself and Miki.

The King Sting was Schwinn's first attempt to capitalize on the popularity of off-road bikes. It was a 26 inch wheeled BMX bike with a readymade five speed drive train. When I finally paid off the bikes, Miki was happy, but my hunger for "light speed" remained insatiable. What I really wanted was one of those custom built, ultra-light ATB's that were the rage of the disgusting yuppie scum in Marin County.

I had been hearing about guys like Joe Breeze, Charlie Cunningham, Steve Potts, Jeff Lyndsay, and Tom Ritchey who were building sweet off-road bikes from chromoly and aluminum tubing, so one weekend I took Dago, my dirty dumpster loin cloth friend, on a visit to a funky bike shop between Fairtax and San Anselmo. The tiny business, co-run by Gary Fisher and Charlie Kelly, sold only one kind of bike--things called Mountainbikes built by Tom Ritchey, the legendary steel-brazing wiz-kid. Gary was a roadie-turned-crusier rider, a top dog at the Repack race that Charlie organized. Charlie later became somewhat renowned as publisher of the world's first off road bike magazine, The Fat Tire Flyer, and the leader of the first mountainbiking rock band, the Aphids.

The visit to the Ritchey Mountainbikes shop was a real pipe dream. Neither my dumpster friend nor I could afford so much as a bullmoose handlebar, but we went window shopping anyway just to make ourselves sick.

Gary insisted that I give one of the bikes a test ride.

The Mt. Tam I tested was a green wonder with tubes that blended into one another through a process called fillet brazing where brass lugwork is meticulously filed by hand to create perfect liquid frame junctions. The high art of Tom Ritchey's work was a real shock and had me committing one of the seven deadly sins in record time: I was coveting my neighbors ass--or at least the thing my neighbors ass was riding on.

I drooled on Tom Ritchey's very fancy Anapurna and Everest models, getting sicker and sicker. I didn't have money to invest, but I could see that the Anapuras and Mt. Everests were high art and worthy of investment just for the sake of investment.

As soon as I returned to San Francisco I wrote a letter to Tom telling him that I thought his bikes were works of art, that they felt and looked more like animals than machines, and riding one was more like riding a horse than a bike. Tom called me a couple of days later to thank me for the creative review. He told me not to spend too much on one of his bikes. "Don't buy the Anapurna or the Everest with all the fancy lug work. It's just cosmetic. The Mt. Tam is the bike to buy. It's exactly the same bike without the fancy lug work."

I didn't tell him that I couldn't afford any of his bikes. I was still in hock for a pre-CBS Fender Jaguar. Guitars. Bikes. What's the difference?

Ritchey's Anapurna and Everest frames are incredibly rare and have become extremely valuable collector's items, just as I suspected they would be. It's ironic that now Tom himself will pay a small fortune to buy them back. Maybe I should call him and tell him not to buy them because all that lug work is just cosmetic. Yea, Tom, buy the Mt. Tam, it's the same bike.

I was told by one of the original Marin Repack riders, that Tom, originally a boy-wonder at building beautiful road bikes, wisely looked to Joe Breeze for direction when it came to frame geometry for his off road frames. Joe Breeze's original Breezer bikes, the very first of their kind, were designed around the Schwinn Excelsior. The ancient Schwinn's success at blasting Joe, Gary, and their buddies down Repack led Joe to copy the frame angles in order to optimize stability, downhill control, and keep vibration at the handlebar to a minimum on his own handbuilt bikes.

Uphill riding at this time in mountainbike history was mostly for getting to the top of the hill to blast back down. Pushing, or a few gears, did the trick just fine. To hell with technical climbing.

Charlie Cunningham's bikes were different. Unlike the steel bikes of Breeze and Ritchey, Cunninghams went REALLY fast up and down. They climbed like mountain goats.

I once met Charlie on a street in San Anselmo riding one of his fat tube aluminum bikes. I recognized his bike, pulled over and screamed at him, "CHARLIE CUNNINGHAM?!"

Boy, was Charlie a character. He had more hair on his neck than on his head, was skinny as hell, and had an Adam's apple the size of a grapefruit. He smiled like a possum, on a constant endorphine high. He ate nothing but pancakes, lived in a treehouse, and rode one of his own raw aluminum bikes everywhere he went.

Charlie was the first person to build a mountainbike with aluminum, and the first to get the weight below twenty pounds. His bikes were home grown high science and his building methods were as weird as his lifestyle. Refinements happened continuously and, as a result, every Cunningham frame was different. It was rumored that he heat treated his bikes in a bonfire and tempered them by tossing them red hot into a pond behind his treehouse. Even if it was a myth, the reality of his frame construction techniques is that the bikes are still being ridden. Charlie's wife Jacquie Phalen rode Cunningham "Balooners" and "Indians" into infamy as the first woman mountainbike champion. Sometimes she rode them topless, sometimes with a stuffed animal on her head. Trust fund babies, rock stars, and unhip real estate agents, fed like bloated pigs on evil Bay Area building and real estate speculation, bought Charlie's bikes for $4000 a piece faster than he could pump them out.

As a starving musician I could only dream of these new age wonders. I stood back and waited for Japan to take over, and, boy, they didn't waste any time at all.

It was 1984 when mountainbikes exploded as mainstream sales items. Fat tire fifteen speed bikes were flying out of the Ross dealership on Stanyan Street in San Francisco faster than Beany Babies out of Toys R Us. Within a year or two every large manufacturer jumped on the bandwagon.

I ended up buying a Diamond Back Ridge Runner, the best, first Japanese import chromoly "ATB" I could get my hands on. The Diamond Back was awesome, a stable and reliable mount, and a real value compared to the Ritcheys,, Breezers, and Cunninghams with their fancy finishes, custom tweaked components, meticulous handbuilt construction, and sky high price tags. I figured that the Diamond Back would serve me well for a couple of years, until I could afford a handmade American ride, and it did just that.

In 1986, while a film student at the San Francisco Art Institute, I purchased a Klein Pinnacle, serial number 257, with a student loan check. When a friend saw the new Klein with its fat tubes and nasty yellow to red to pink fade paint job, he had to have aluminum too. He sold me his camoflaged Ritchey Commando for a song and a dance to finance a new Cannondale. This particular Commando was the very first of its breed, and over the years I grew to favor it over the Klein.

I still own the Klein and the very precious Ritchey. I cherish them both and ride them occasionally. The Ritchey Commando has classic early mountainbike geometry with a slack 68 degree head angle and very long 18 inch chainstays. It rides like one of the old English paratrooper bikes that were dropped from planes to be used in field combat in the second world war. The Commando likes for you to stay in the saddle at all times and feels like it has suspension at both ends. It's light, compliant, stable, and begs you to try anything. After nearly fifteen years the thing still just feels right. It loves to descend, and as long as you remain seated it will climb almost anything. Stand up and "whoooosh," the rear wheel gives way.

The Klein was a revolution at the time it was introduced with its dropped top tube, filed aluminum frame construction, square to round, short chainstays, and steep angles. I have never ridden a better bike for picking your way at speed through tight singletrack or bunnyhopping logs, but take it downhill on hardpack or loose gravel and you may find yourself screaming for Mama. The Pinnacle's aluminum construction is STIFF, and its geometry is quick and unforgiving. The combination can be lethal. I have x-rays to prove it. For some reason, whenever the bike is pointed down anything steep and loose, the rear end wants to be the first to the bottom.

Standard rigid mountainbikes really haven't gotten much better since the mid 80's. Top tubes got a tad longer. The angles steepened a bit. The components got lighter. Shifting improved. Titanium and carbon fiber raised their expensive heads, but that Ritchey Commando and Klein Pinnacle were, and still are, so close to perfection that I would choose to ride them above just about any other fully rigid bike, new or otherwise.

But that was then and now things go bounce.

Like most off-road innovations the concept of suspension had been tried almost a century earlier in many shapes and forms, but in 1990, with the backing of years of off-road motorcycle technology, Paul Turner's air-oil Rock Shox front fork took the world by storm and upped the ante in high performance Big Time.

Doug Bradbury, the builder of legendary Manitou fames in the 80's, fabricated his aluminum miracles in a garage just above Colorado Springs. His bike's handling was so dialed, and the aluminum construction so smart and refined, that the early Manitou bikes were in a class all their own, touted by many to be the best off-road bikes of their time. When Doug got wind of the idea of putting front suspension on a mountainbike he wisely sought to make forks that were simple, light, stiff, and easily tunable. Instead of the complicated air spring and oil damping of Turner's units, he opted for elastomers, the same spongy things used in my Independent skateboard trucks in the 70's. Elastomers had natural compression and rebound damping, characteristics that made them nearly ideal for a soaking up bumps in a lightweight and easily serviceable mountainbike fork.

When boy wonder, BMX-turned-mountainbike racer, John Tomac, began to race on a Manitou fork in 1990 heads began to turn. When, in that same year, Ned Overend took the cross country World Mountainbike Championship on a Rock Shox fork, and Greg Herbold took the downhill championship on a Rock Shox as well, the fully rigid mountainbike began to die off on race circuits. Racers on rigid bikes, trying desperately to follow those with front suspension, were beginning to break collarbones and find religion just trying to keep up. Race teams began to spend as much money on tuned front suspension as they did on frames.Click here for chapter 2.

Click here to return to STORIES index.

Click here to return to HOMEPAGE index.

To speak to Lee Bridgers or to book a tour call (435) 259-6419 or write Dreamride Mountainbike Tours, P.O. Box 1137, Moab, UT 84532.

For email contact information click on:

CURRENT DREAMRIDE EMAIL ADDRESS

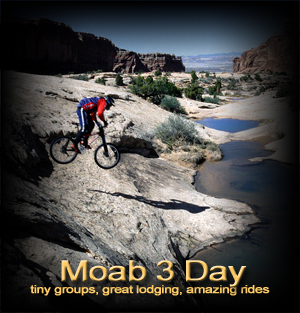

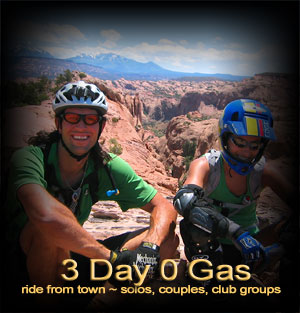

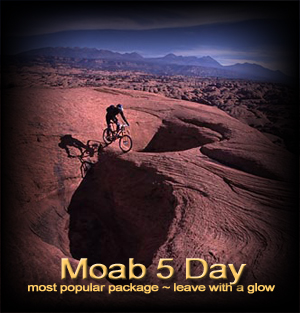

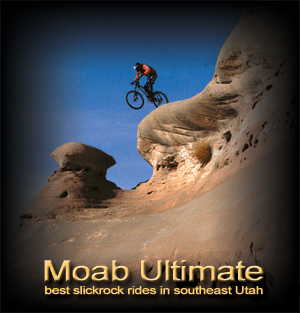

Most requested packages.

Use the printed links on the left side of this page to access all of Dreamride's vacation packages, or short cut to our most popular packages listed below on the right side of the page.